Where does a story begin?

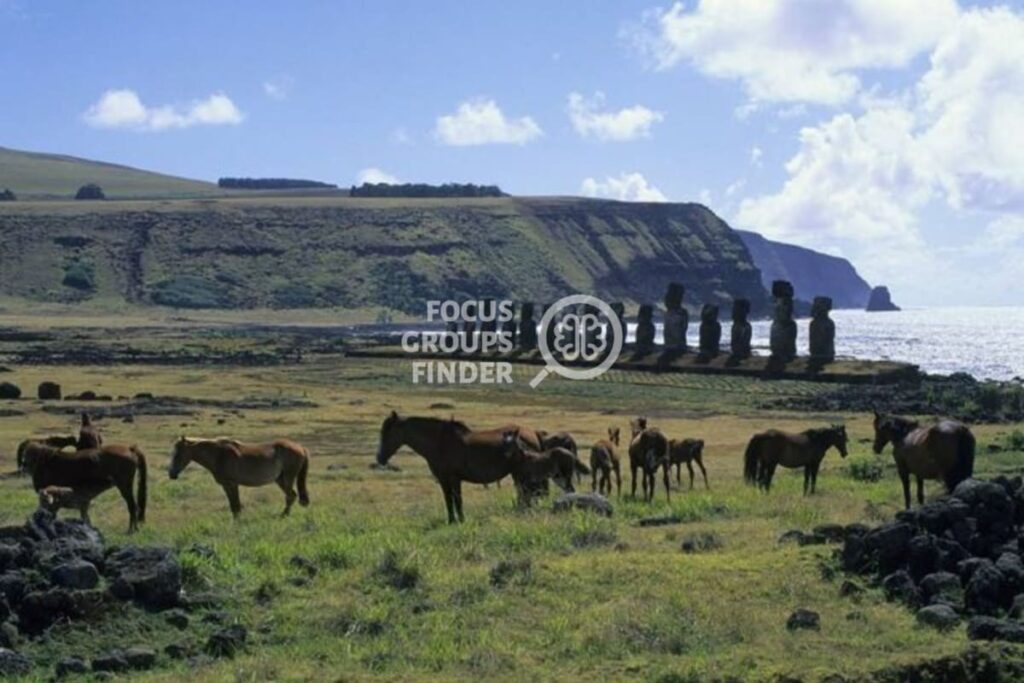

This one, given that it is something that came from the ground in one of the most remote places on the planet, perhaps must start with the eruption of three massive volcanoes eons ago in the southern Pacific Ocean, which formed an island of 163.6 km² which, except for a minor fertile area, is lava with a thin layer of soil.

Or maybe the beginning of this story should be a dream; one in which a spirit traveled in search of a new home for the legendary overlord Hotu Matuꞌa and his people, and found a triangle with a hole (the crater of a volcano) called ” Te Pito’ or the Kainga “, meaning “Center of the Earth”.

After sending 7 men to find it and receiving, on his return, the news that it was a distant paradise, Hotu Matuꞌa set sail with two ships full of settlers. The civilization that prospered created beauty and enigmas in that speck of lava between the waves that put what is known as Rapa Nui or Easter Island on the map.

Although perhaps it is more appropriate to start this story with the curiosity that aroused in a scientist, hundreds of years later, that the natives did not suffer from tetanus, despite the fact that they walked barefoot in a land full of horses, the conditions ideal for infection.

That is why the microbiologist Georges Nógrády, one of the 40 doctors and scientists who had arrived from Canada in December 1964 to study the culture, environment and diseases of this exceptional place, divided the island into 67 plots and took soil samples. of every one of them.

He only found tetanus spores in one of the samples, but fortunately the vials with bits of Easter Island territory reached the hands of scientists from the Ayerst pharmaceutical firm in 1969.

“Fantastic Activity”

For Ajai Sehgal, director of Data and Analytics at the Mayo Clinic, the story began when he was a child .

“When I was about 10 years old, I went with my father to his work – in Ayerst’s laboratory in Montreal – and asked questions,” he told BBC Mundo. “He didn’t have the background to understand everything, but he knew he was in the drug discovery business and he understood what he was trying to do.”

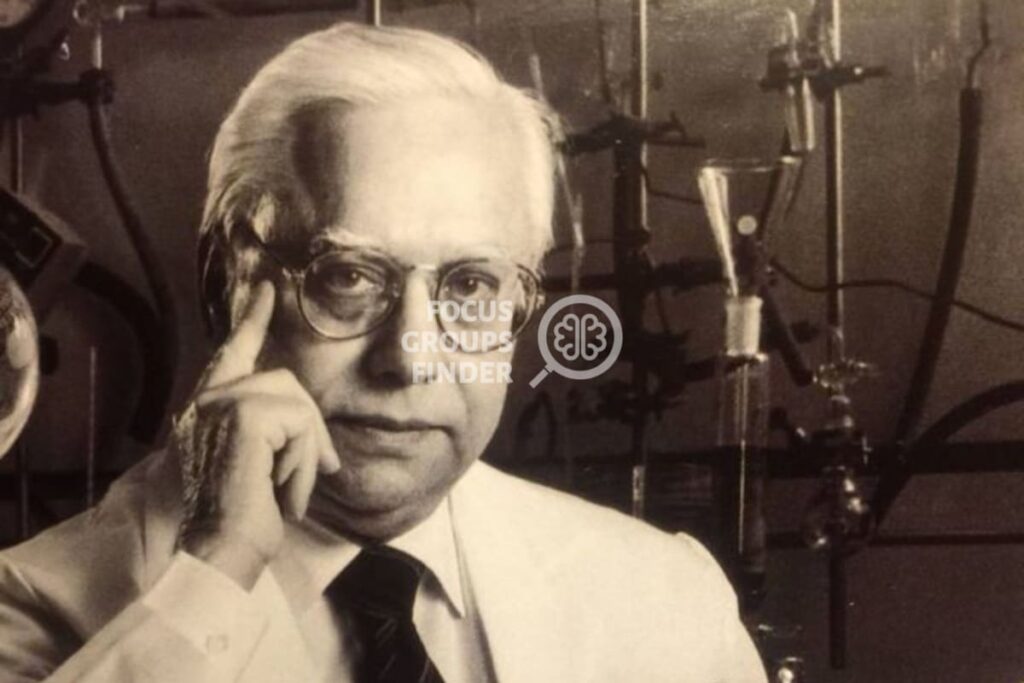

What his father, microbiologist Surendra Nath Sehgal , and his colleagues were trying and succeeding in doing was isolating microorganisms from the soil of Easter Island, coercing them to reproduce, and then analyzing the substances they produced.

One of them, the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus , produced a compound, a natural product isolated in 1972, which they called rapamycin, in honor of Rapa Nui, a name given to Easter Island by its indigenous people .

They found that they were very good at inhibiting fungal growth, but there was a problem.

“It was also immunosuppressant so it left the part of the body treated defenseless.

“Imagine you have a fungal infection on your hand and you apply rapamycin cream – it kills the fungus but will probably give you a bacterial infection,” Ajai explains.

However, Sehgal sensed its value.

“He knew that it had a very aggressive immunosuppressive activity, and also that it was a very safe drug because the toxic level could not be found.

“That is to say: normally what you do is give a mouse more and more and more doses of the drug until it dies, and so they find the maximum safe level. But in the case of rapamycin they never found the toxic level because the mice never they died,” Ajai clarifies.

At that time, the immunosuppressants that were available “were all highly toxic” .

Also, while it seems counterintuitive that something that bypasses a defense against tumors could be a likely anticancer drug, dr. Sehgal noted that this compound seemed to have novel properties in that it could stop cells from multiplying .

At a time when all chemotherapies killed living cells, having something like this could be very beneficial.

Sehgal sent a sample of the compound to the US National Cancer Institute (CIN), where they noted that it had “fantastic activity” against solid tumors.

Work in that direction was showing promising results when it was abruptly stopped .

Disobedient

In 1982 Ayerst decided to close his Montreal research laboratory, and move a few of his scientists to his facility in Princeton, New Jersey, United States.

Dr. Sehgal was one of them, but rapamycin did not meet the same fate.

It was simply a business matter. The company did not see a lucrative future for it as a drug, so it decided to end the project.

The order was to undo everything, file it and forget it.

“My dad did the opposite ,” Ajai recalls.

Knowing that the closure of the Montreal facility meant that he would not have access to the large-scale fermenters needed to produce rapamycin, Dr. Sehgal prepared a batch to take back to Princeton.

“He put it in little glass jars, took them home and put them in my mom’s freezer, marked with a label that said DO NOT EAT because it looked like ice cream.”

Ajai found out about his dad’s mischief when he went to help pack for the move to Princeton and was tasked with making sure his precious (and clandestine) cargo made it safely to their new home .

“I was 20 years old and an officer in the Canadian Armed Forces at the time. But I did it for my father.

“I put everything in an ice cream container, I bought dry ice because we had to unplug the freezer to put it in the dump truck, I sealed everything with duct tape and put holes in it because when dry ice melts it creates carbon dioxide, and I didn’t want to that it became a bomb, and that’s how it went.

The plan worked.

“The freezer arrived in the basement of his new home in Princeton, unexploded and with all the samples intact, and there it stayed for about 5 years .”

a new beginning

By the end of the 1980s, organ transplants were already ceasing to be science fiction. But the great obstacle was still the immune system, which was activated and attacked the foreign part of the body, putting the lives of patients at risk due to rejection.

An immunosuppressant was needed, but do you remember that the approved ones were dangerous and ineffective?

By then, the company Sehgal worked for had changed, and he brought the idea to new managers at the merged Wyeth-Ayerst to explore whether rapamycin might be the solution.

From the pharmaceutical point of view, the time had come to resurrect the project: there was a lot of gold at the end of that rainbow .

“‘But,’ they told him, ‘how are you going to continue your work if all the samples have been destroyed?’

“‘Perhaps not,’ he replied.

“At the time he had no idea if the samples that were in the freezer were still alive, if he could make more rapamycin from them: it’s like sourdough for bread, or the starter culture for yoghurt.

“In the laboratory, he verified that they had survived. From what my father kept, new batches were created to carry out the studies ,” says Ajai.

And if that was not enough…

After so many years of believing but not being able, in 1987 Sehgal had the means to once again bring to light what had been unearthed on Easter Island.

After several successful clinical studies, in 1999 the FDA Advisory Committee made a unanimous recommendation for the approval of Rapamune, the immunosuppressant developed by dr. Sehgal and his staff that have brought multimillion-dollar profits to Wyeth-Ayerst and, since 2009, to Pfizer.

But Sehgal didn’t just want to develop rapamycin’s potential as a drug.

He had convinced the CIN to revive their research on its effect on malignant tumors and wanted to understand how it worked… why did it ‘freeze time’ wherever it touched?

To that end, he sent samples and information on the compound to various study centers.

The now biologist Daniel Sabatini – who in 1992 was doing his doctorate in Medicine and Philosophy (MD-PhD) – came across one of those packages from Dr. Sehgal, with a note that said: “Good luck!”.

He certainly had it.

“He discovered the mechanism of action of the drug: how it works,” says Ajai.

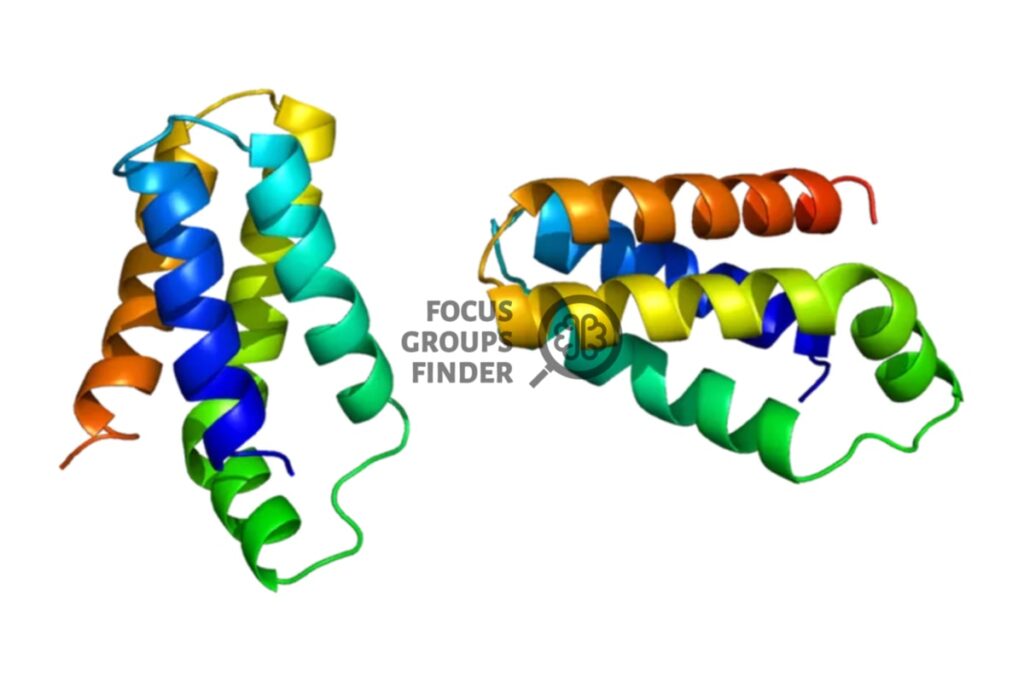

And efforts to understand it led him and other scientists to independently identify a protein known as mTOR , revealing fundamental insights about our biological nature.

What’s that???

“Imagine a construction site. The general contractor is in charge of telling the plumbers, carpenters, electricians, masons, etc. what to do. If there are enough bricks and cement, he orders the walls up; if the pipes don’t they are not going to arrive until tomorrow, he tells the plumbers to call off work.

“mTOR does that for the cell. It’s a sensor; it detects if there are nutrients and it tells the cell to grow or not to grow .”

It is a fundamental indicator: if, for example, cell division begins without the optimal levels of amino acids, glucose, insulin, leptin and oxygen to fuel the process, the cell dies instead of multiplying .

What rapamycin does is trick the body’s cells into thinking there are few nutrients when there are, stopping growth.

And what scientists are beginning to understand is that this is not the only thing that happens.

Going back to the construction site, while it is going on, there are packages here, garbage there, but if suddenly everything has to be suspended due to lack of materials, the contractor will tell the workers that, while they arrive, clean and organize the place.

Well, it turns out that when rapamycin tricks mTOR, it does the same thing with cells: it tells them to clean themselves, as it turns out that they accumulate deposits of waste that they don’t eliminate and over time make them less efficient.

That’s basically getting old.

“The cell is cleaned and repaired because it thinks it has no supplies,” Ajai says.

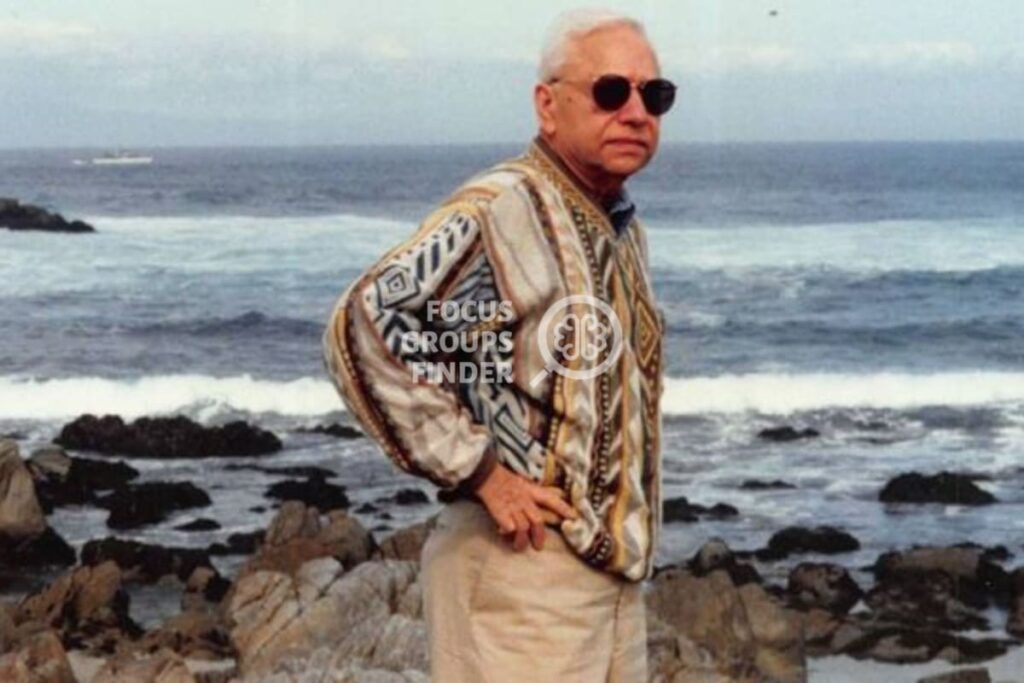

What happened to Ajai’s father?

Dr. Sehgal received the admiration of the medical world and the thanks of millions who had been given longer lives by rapamycin.

He learned about mTOR and the answer to what intrigued him: why it froze time. But he did not know about the cellular cleaning that he promotes. However, even in this he was somewhat of a pioneer, doing with his body what many researchers would do – and continue to do – with animals in laboratories.

In 1998, he was diagnosed with stage IV metastatic colon cancer after a routine colonoscopy.

“After the first year of chemotherapy that he couldn’t tolerate – it was killing him – he decided to stop it and start taking rapamycin .

“He knew that it suppressed tumors; the tumor is a rebellious cell that grows without control and rapamycin prevents it. He was experimenting on himself but they had only given him six months to live, so he could not make the situation much worse,” points out his son.

“He got better. In fact, he lived a good life for 4 years , he was able to meet his grandchildren and they him. And one day, on a trip to India to give lectures, he told my mother: ‘I feel fine, but I’ll never know if it’s the rapamycin that’s keeping me alive unless I stop taking it.’

“And that he did.

“In a matter of 6 months, the cancer invaded his entire body and that was it, it was over.

“On his deathbed he told me, ‘The stupidest thing I ever did was stop taking my medicine.’ But that was his nature . He was a scientist and he needed to know.

“Also, he was trying to convince others to start clinical trials for cancer, and he was excited, well, basically what he did, because he documented everything, that’s how it was.”

” He worked to the end . The day before he died, he was writing an article in bed advocating the antitumor properties of rapamycin.”

Doctor Suren died on January 21, 2003.

The uses of rapamycin continue to multiply, as an immunosuppressant and in different types of cancer and other diseases. At this time, there are dozens of studies underway exploring its potential to lessen the negative consequences of old age.